Lemon Tree & Public Sport Park

Context and Motivation

In the late 2000s, the fertile plains of the Vega Baja del Segura, once one of Spain’s most productive citrus-growing areas, were undergoing a silent transformation. The pressure of urban expansion was quickly erasing the orchards that had shaped both the landscape and the local culture.

Having grown up helping my grandfather prune, irrigate and harvest lemons on weekends, I could see first-hand what was being lost: not only trees, but knowledge, shade, microclimate and identity.

By 2007, I began my final degree project with one urgent question:

Could contemporary architecture and landscape design help preserve the agricultural heritage of the Vega Baja while responding to new urban needs?

The result was The Lemon tree park, a vision for a productive public landscape where orchards, sport, and community life could coexist through an intelligent management of water, climate and topography.

Architecture as a bridge: re-imagining orchard landscapes through water and community design

Pedro Orenes García

Design Vision

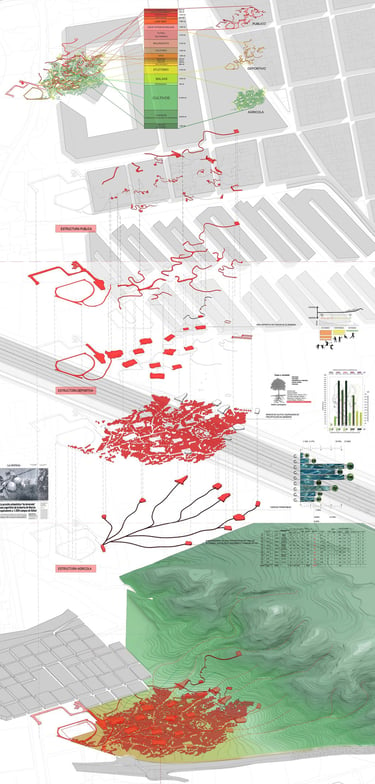

The project was conceived as a living organism rooted in the cycle of water. Every path, basin, and plantation line derived from the natural slope of the terrain. Instead of treating the orchard as obsolete land waiting to be urbanized, the proposal reimagined it as a hybrid infrastructure:

a park that produces, a field that cools, a landscape that teaches.

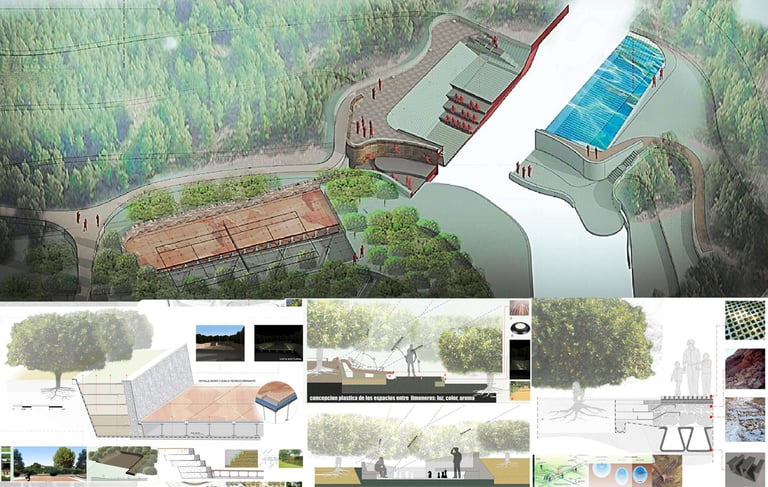

The idea was to transform 70,000 m² of abandoned agricultural land, located between the consolidated urban fabric of La Alberca and the regional park El Valle y Carrascoy, into a public green system that could:

Rehabilitate traditional irrigation channels and collect rainwater through new storage basins.

Integrate sports and recreation areas without erasing productive land.

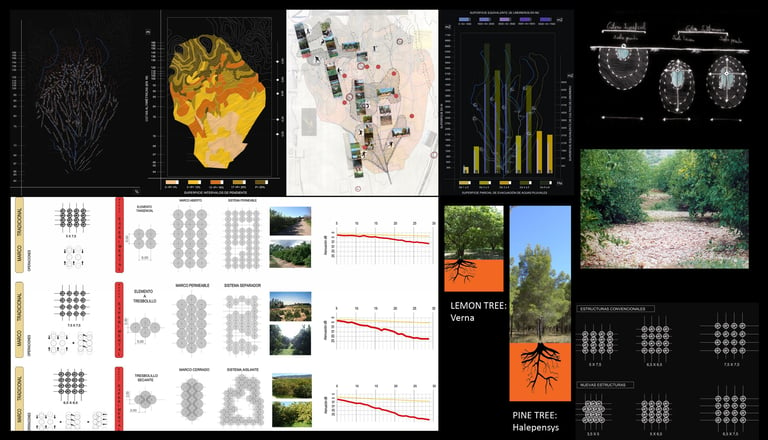

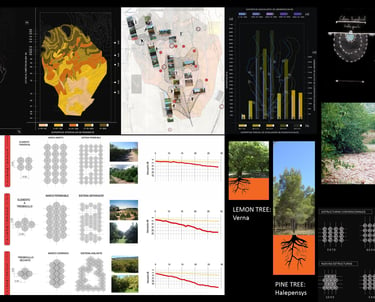

Use trees as architectural elements, natural barriers for sound, privacy and microclimatic regulation.

Create a resilient landscape capable of mitigating heat and generating local employment in sustainable maintenance and agro-tourism.

At a time when “sustainability” was still mostly discussed in terms of materials, this project focused on the metabolism of the territory: water, soil, vegetation and economy as a single system.

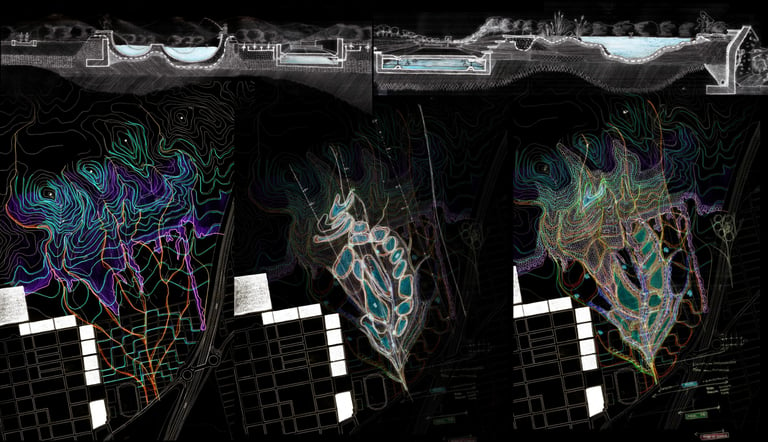

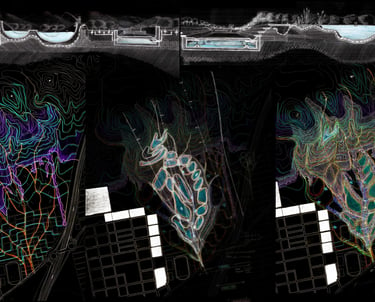

From Data to Design

The design process began with fieldwork: mapping slopes, measuring rainfall, and identifying zones suitable for water retention. A detailed pluviometric study guided the placement of accumulation basins, capable of storing stormwater during the rainy season and holding other uses, an outdoor cinema or recreation areas during the dry months.

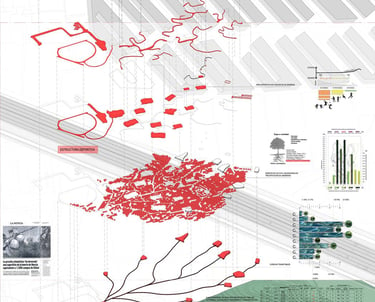

Using topographical logic, the site was organized into three main layers:

Upper layer: collection basins and pine forest buffer zones.

Central layer: lemon orchards arranged in productive bands.

Lower layer: sports courts, open lawns, and pedestrian paths following the terrain’s natural gradient.

Permeable surfaces, underground drainage layers and experimental perforated pavements were designed to capture runoff from the sports courts, a literal translation of “playing with water.”

The architectural program included lightweight service buildings, warehouses for agricultural tools, small sports facilities, and shade structures. Every element was designed with low energy demand and bioclimatic principles: orientation, cross ventilation and local materials.

Beneath the beauty of the orchards lay an unseen technological system, a “landscape machine” that managed rainfall, reduced heat, and recharged groundwater.

Technological references were drawn from advanced citrus production systems used in the most innovative agricultural regions, adapted here to an urban-ecological context.

Legacy and Reflection

When the project was presented in 2009, it proposed a radical alternative to the conventional suburban expansion that was already replacing the orchards. Fifteen years later, the built reality in that area, now known as Montevida, confirms what was feared:

dense housing, higher average temperatures, reduced rainfall and the loss of local agricultural identity.

The Lemon Tree Park anticipated these effects by proposing a different logic of growth, one that treated green infrastructure as the core of urban development, not its leftover.

Looking back today, the project remains a personal and professional milestone. It represents the moment when my understanding of architecture shifted from buildings to systems, from the object to the environment, from construction to regeneration.

It was also a declaration of principles:

that sustainability is not a trend, but a way of thinking long before it becomes urgent.

Final Architecture Project

Interested in collaborating on landscape- & water-based urban projects? Contact me